Investment Manager’s Report: Summary

An extract from the full Investment Manager’s Report

The financial information set out below does not constitute the company's statutory accounts for the years ended 30 April 2024 or 30 April 2023 but is derived from those accounts. Statutory accounts for 2023 have been delivered to the registrar of companies, and those for 2024 will be delivered in due course. The auditor has reported on those accounts; their reports were (i) unqualified, (ii) did not include a reference to any matters to which the auditor drew attention by way of emphasis without qualifying their report and (iii) did not contain a statement under section 498 (2) or (3) of the Companies Act 2006.

The full Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ending 30 April 2024 can be found here.

Market Review

Equity markets delivered strong returns during the Trust’s fiscal year as inflation trended back towards target, unemployment remained low and economic growth surprised to the upside. The MSCI All Country World Net Total Return Index in Sterling returned +18.1% during the fiscal year, while the S&P 500 and the DJ Euro Stoxx 600 indices returned +23.3% and +9.0% respectively. The ‘goldilocks’ combination of disinflation and strong economic growth was entirely at odds with investor pessimism and bearish positioning at the start of the fiscal year, which reflected a torrid 2022, adverse financial conditions, above-average valuations and the allure of significantly higher risk-free rates. Investors poured $1.3trn into money market funds during 2023, 10x more than flowed into equity funds.

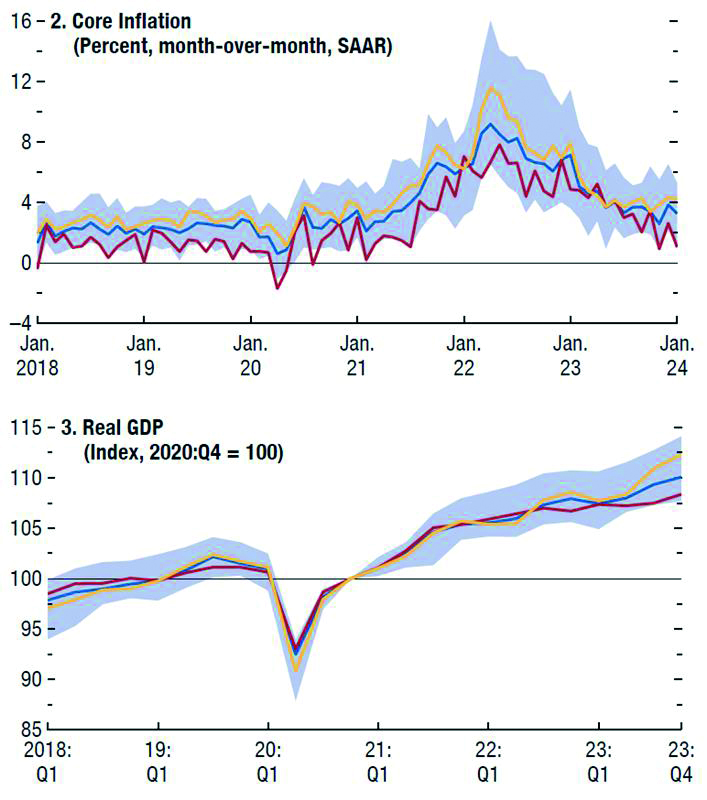

The fiscal year began amid the fallout from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse. Decisive policymaker actions prevented contagion and reminded investors that in extremis the so-called ‘Fed put’ (an assumption that if necessary the Fed will step in to support financial markets) was alive and well. Global markets rebounded from lows in March to almost recover their December 2021 highs by the end of July 2023, supported by resilient consumer spending and strong labour markets, even as central banks hiked rates aggressively. Inflation trended down (‘core PCE’ declined from 5.2% in 2022 to 4.1% in 2023 and is forecast to reach 2.6% in 2024) without triggering a recession or even an increase in the unemployment rate, which remained below pre-pandemic levels in many countries.

Ben Rogoff

Partner, Technology

Alastair Unwin

Partner, Deputy Fund Manager

Strong equity market returns depended on the (surprising) fact that aggressive rate hikes did not derail the economy. Instead, US real GDP growth of 2.5% in 2023 (and expectations for 2.7% in 2024) significantly exceeded expectations at the start of 2023 (1.4% and 1.0% for 2023 and 2024 respectively). This ‘goldilocks’ scenario was tested during the fiscal year, however, as US bond yields touched 5% in October 2023 on a narrowly-averted US government shutdown, increased US Treasury issuance, a ratings agency downgrade and emerging ‘higher for longer’ interest rate commentary from central bankers.

The rise in yields proved short-lived and they retraced to c3.9% by the end of the calendar year, spurring a cross-asset rally. Favourable seasonal trends were buoyed by investors’ growing hopes of a soft landing (where inflation comes down without a significant increase in unemployment). Markets took dovish commentary from Fed policymakers and supportive inflation data as a signal that the Fed had completed its hiking cycle and began to price the first rate cut in March, with expectations for six or seven 25-basis-point interest rate cuts by the end of 2024.

The New Year (and final third of the Trust’s fiscal year) presented challenges as US 10-year Treasury yields rebounded to c.4.6% in April as labour markets and economic data remained firm, and inflation readings came in a little hotter than expected. This pushed out market expectations of the timing of the first Fed cut from March to November and put upward pressure on real yields (government bond yields adjusted for inflation), which moved from 1.7% coming into the year to c.2.2% by the end of April.

Despite still being incomplete, the rise and fall of inflation has been remarkable, demonstrating that credible central banks can contain inflation by controlling inflation expectations, rather than just slowing down the economy. The Fed also enjoyed notable tailwinds including productivity gains, benign weather and a tepid Chinese recovery. We have previously argued (in our 1945-1947 inflation parallel) that many Covid-related imbalances would probably have resolved themselves eventually, but the historic path taken by the Fed reflected the uniqueness of the post-pandemic episode. Larry Summers, a former Treasury Secretary, described the Fed’s actions in the two years after 2021 as a “less than 1% probability set of actions relative to what the market expected”.

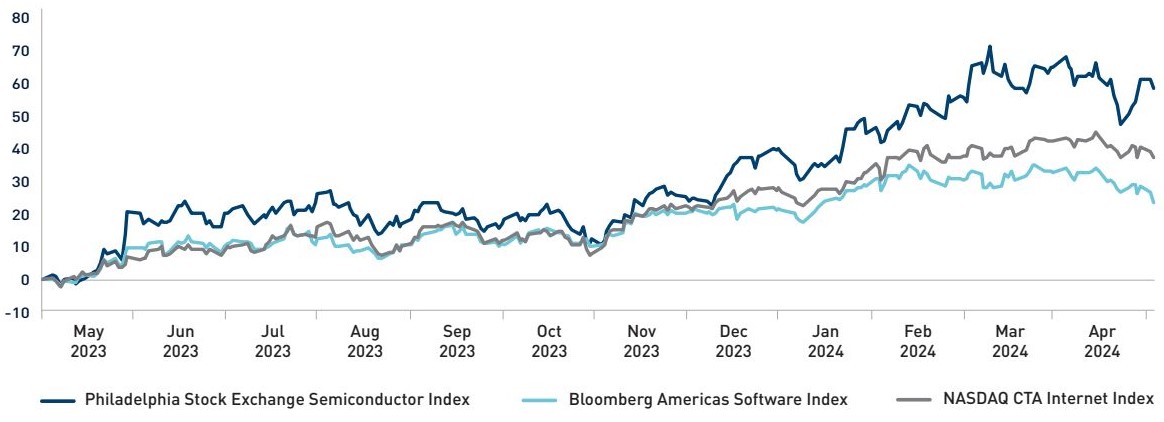

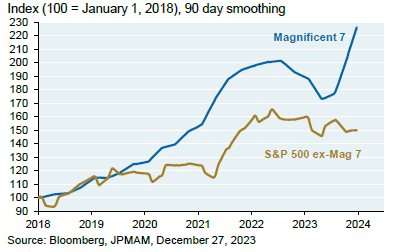

An inescapable feature of equity markets during the fiscal year was the dominance of a select group of mega-cap technology stocks, the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ - latterly the ‘Fab Four’ (or Five) - which returned +60% combined in USD terms, according to Bloomberg. These returns emerged following a disastrous calendar 2022 when the group declined -45%, and FY24 returns were driven almost entirely by positive estimate revisions. Their dominance of equity returns (and indeed profit pools) has been felt more widely across the market as large cap stocks (Russell 1000) outperformed small cap (Russell 2000) by 10ppts during the fiscal year, 32ppts over the past 3 years and 50ppts over the past 5 years.

Source: IMF, April 2024

Source: Bloomberg

Technology Outlook

Earnings Outlook

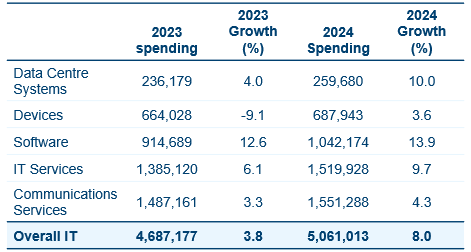

Having stabilised in 2023 with growth of 3.5% y/y, worldwide IT spending is expected to reach $5.1trn this calendar year representing an increase of 8% y/y, in current dollar terms. This represents a notable acceleration and an upward revision from the +6.8% forecast in January. While Gartner believe it will take until 2025 to translate into enterprise budgets, it is clear that Al has already become a corporate imperative with c45% of CIOs planning to adopt Al within 12-24 months. Strength expected in datacentre spending (+10% y/y) suggests that the digital groundwork for Al is being built ahead of enterprise adoption, led by hyperscalers. Likewise, an expected rebound in devices, following two very weak consecutive prior years, is predicated on Al-related product cycles.

For 2024, the technology sector is expected to deliver revenue growth of 9.3%, while earnings are expected to increase by 18% which would represent the best year for earnings since 2021. These forecasts are well in excess of anticipated S&P 500 market growth, where revenues and earnings are pegged at 4.9% and 11% respectively. The technology sector’s outperformance is expected to continue in 2025 with early forecasts for 10.8% / 13.8% comfortably ahead of market expectations (5.8% / 9.5%). While macroeconomic conditions may create crosscurrents, we believe technology fortunes this year will be determined by the path of AI progress.

Valuation

The forward P/E of the technology sector has expanded during the past year. A year ago, valuations had recovered to c24x forward P/E, having ended 2022 at c.19x. Since then, valuations have increased further as technology earnings and stock performance (especially Mag-7) ‘crowded out’ the broader market. At time of writing, technology stocks trade at 26.5x, well ahead of five (23.9x) and ten-year (20.3x) averages. This reflects the arrival of AI as an investment theme and a much improved inflationary backdrop. The premium enjoyed by the sector expanded during the past year with excitement around AI resulting in the sector making post-bubble highs (1.4x the market multiple), levels last seen briefly during the pandemic period. At time of writing, this premium has fallen back to c.1.3x – at the high end of the post-bubble range. While this suggests less valuation upside in the near-term, we believe that AI represents a unique moment for the technology sector such that the post-bubble range (between 0.9-1.3x) may no longer be valid.

Source: Gartner, April 2024

Source: Ned Davis, 31 May 2024

Magnificent 7

However, the valuation question is greatly influenced by a select group of mega-cap stocks that – as well as driving returns last year – also dominate technology indices. As such, this year we present some high-level thoughts on the so-called ‘Mag-7’ given the implication for future returns, prospects of a broadening market and, of course, our own positioning.

While 2023 proved a remarkable year for the group, returns are highly sensitive to the starting point; since the beginning of 2021, Mag-7 – at time of writing - has only outperformed the S&P 500 by 10%. At time of writing, the group sports a premium valuation; a forward P/E of 29.6x as compared with 20.9x for the overall index and 18.6x for the remaining 493 S&P 500 (SPX) companies. However, Mag-7 accounts for c.29% of SPX market cap and is expected to generate c.22% of SPX net income. One might argue a little extended, but very clearly far from bubble territory. Moreover, the group is expected to deliver three year compound annual revenue growth of 12% versus 3%, higher margins (22% vs. 10%) and a greater re-investment ratio (61% vs. 18%) than the SPX493. This superior profile has shown little sign of abating as in Q1 2024, expected S&P 500 earnings growth of +6% y/y is expected to come from Magnificent 7 earnings growth tracking to +48% y/y while the remaining ‘S&P 493’ are forecast to deliver -2% y/y. These metrics reflect the group’s uniqueness, with each member dominating large markets, enjoying scale advantages or natural monopoly status while investing heavily in new opportunities to avoid the so-called innovator’s dilemma. Most also have strong AI stories in our opinion, and all are what we consider non-fungible companies and stocks. As such, we expect to retain sizeable positions in the largest stocks in the benchmark over the coming year, assessing each on its own merits and not defaulting to a market broadening narrative, even if we (and other active managers) strongly desire it.

Source: Bloomberg, JPMAM, December 27, 2023

Next generation / longer-duration stocks

Next-generation valuations have also expanded as we predicted in last year’s Annual Report when we suggested it was ‘highly likely’ that we had already seen the lows. Since then, an improved inflation outlook and moderating cloud optimisation headwinds have seen software valuations recover to c.7.0x forward EV/sales, having bottomed at around 5.1x (and peaking at 16x in 2021). According to KeyBanc, this leaves them ahead of five and ten-year pre-covid averages of 6.1x and 7.2x respectively. Higher growth stocks have experienced a greater valuation recovery with companies growing revenues above 20% today trading at 10.9x forward EV/sales; down 62% from highs but well ahead of pre-COVID five- and ten-year averages of 7.8x and 7.0x respectively. In contrast, unprofitable growth stocks have recently made new valuation lows, trading at less than 3.0x forward EV/sales.

Survival of the fittest

The partial recovery in software valuations (and related lack of market interest in unprofitable growth stocks) reflects a slower growth environment ameliorated by higher industry margins. This year, the median software growth rate is forecast at 14-15% as compared to 17% in 2023, and 26-27% in 2022. However, the adoption of the so-called PE playbook, as highlighted last year, has become the norm for most software companies and has been rewarded by the market. Unlike prior downcycles, the recalibration was rapid, reflecting unique post-pandemic challenges – bloated and disconnected workforces, waning product and corporate relevance, the end of ‘free money’ and, more recently, the birth of genAI. The focus on more profitable growth has seen the median software company’s free cashflow margin expand by a remarkable 1500bps from c.5% in 2019 to c.19-20% in 2024E. This recalibration has seen the best companies become better versions of themselves. For instance, while CrowdStrike stock has more than recaptured 2021 highs, over the past c.3 years it has grown revenues from $1.1bn to $2.9bn while expanding operating margins (OMs) from 10% to 19%. ServiceNow – recently at all-time highs – has grown revenues from $5.5bn to $8.5bn while expanding OMs from 25% to 29%. In addition, both companies should be able to use AI to deliver further margin improvement as well as monetise the technology via AI-enhanced product lines.

Against this backdrop, unprofitable companies are not merely anachronistic – they represent a pool of companies unwilling or (more likely) unable to deliver margin expansion. They are former pandemic / WFH winners, derivative plays on now unloved themes, SPACs, or companies that might have changed the world in 2040 had zero interest rates prevailed. They are the broken toys used by equity investors to play themes that didn’t last or never happened. Some may yet reinvent themselves, but history suggests most will disappear, to be combined, reconstructed, or dismantled by private equity. As such, we continue to tread tentatively in longer-duration stocks, doing our best to avoid the siren call of ‘cheaper valuations’.

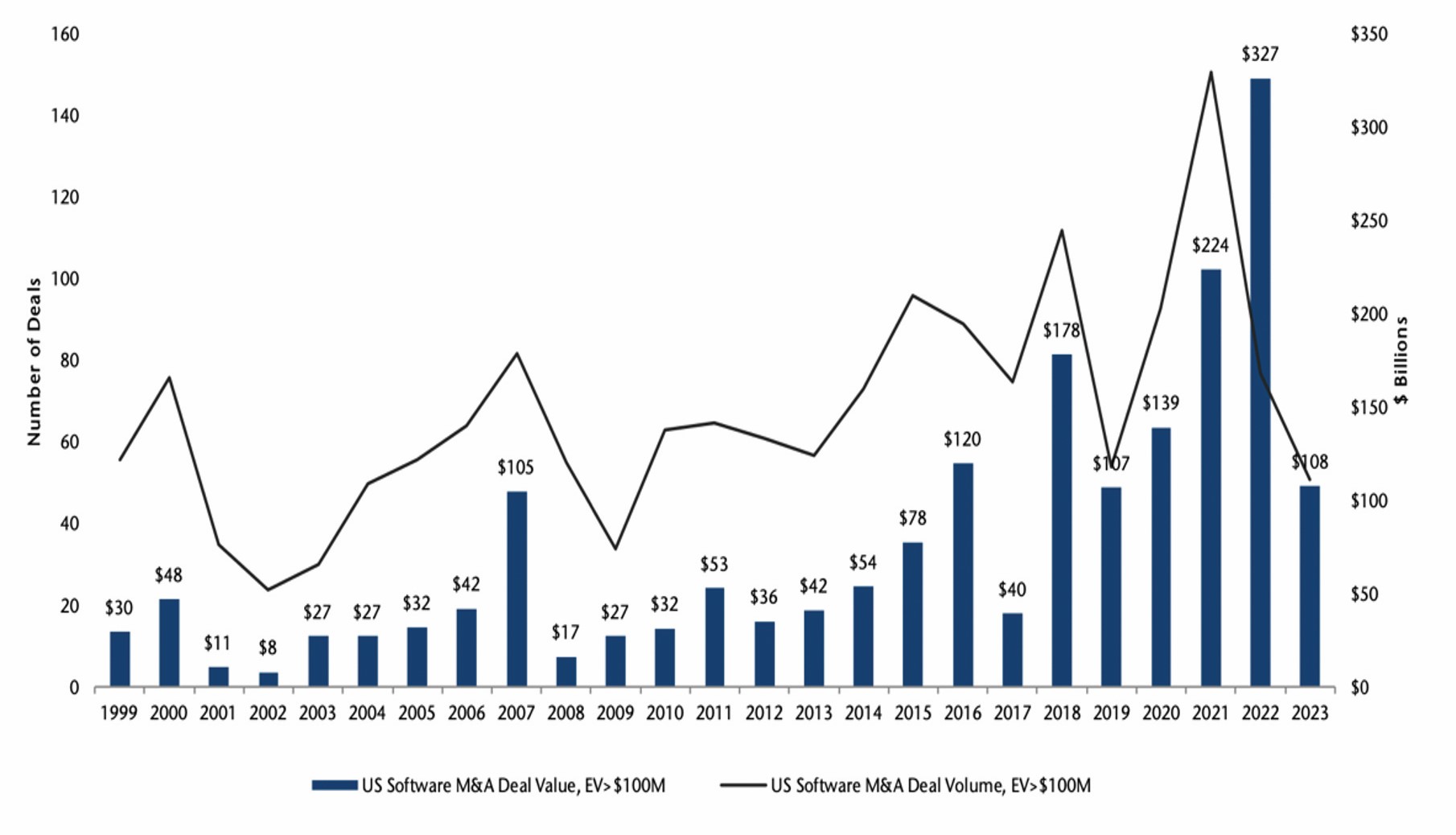

More M&A activity likely

Following a dismal 2023 for M&A, this year has got off to an encouraging start. After a notable absence of strategic M&A, 2024 has already seen HP announce the $14bn acquisition of Juniper Networks, while Synopsys and Ansys are set to combine in a $35bn stock and cash transaction. More recently, IBM scooped up Hashicorp for $6.5bn, representing c.8.5x EV/CY25 revenues and a 42% one-day premium, while in the UK, there was recently a bidding war between Viavi and Keysight for Spirent. In addition, private equity is likely to remain active with c.$2.5trn in ‘dry powder’ having acquired Alteryx, New Relic and most recently, Darktrace. We expect AI to play a part in greater M&A too, as point solution companies continue to struggle versus platforms with LLMs likely to prove highly disruptive to pre-GenAI vintages. Nonetheless, a recovery in M&A activity should provide some downside support to current valuation multiples.

Cloud / AI Update

Cloud reacceleration

After decelerating for ten quarters, public cloud revenue growth finally reaccelerated in Q4’23 reflecting the combination of waning optimization activity and ramping AI workloads. In Q1’24, aggregate cloud revenue growth reaccelerated 3ppts sequentially to +24% y/y – remarkable given a greater than $210bn industry revenue run-rate. We are hopeful that the post-COVID optimization process is largely complete, a view supported by CIO surveys that suggest cloud spending should more closely track consumption from here. More importantly, AI workloads are beginning to ‘move the needle’ with AI called out as a meaningful contributor at Microsoft (7pts of Azure revenue growth in its most recent quarter) and Amazon (“multibillion-dollar revenue run rate” in AWS). We expect these tailwinds to grow stronger as the public cloud remains a key conduit for accessing AI. Foundation models with ever greater parameter counts require larger clusters of connected AI servers, while the compute requirements of AI applications are said to double every 3.5 months; both needs fit well with cloud flexibility and scalability.

A new architecture for AI

The hyperscalers also have the ‘deep pockets’ required to invest in AI infrastructure, which due to extreme performance required by AI training is heralding a significant shift in IT architecture from serial to parallel compute. We consider the architectural break far more significant than the transition to cloud from on-premise compute. This is apparent from an AI server bill of materials (BOM) said to be 25x greater than a general purpose cloud server. A useful parallel for this might be comparing a Toyota Prius with Formula 1; both are cars, but one is designed for general purpose and efficiency (cloud), the other for extreme performance (AI).

Unprecedented growth

The nascent ‘AI war’ that began a year ago (when Microsoft looked to leverage its OpenAI relationship to challenge Google’s search business) has given way to something far more significant, accompanied by an unusual urgency that feels reminiscent of the 1990s. Having increased by c.5% during 2023, datacentre capex will materially accelerate this year with all of the US hyperscalers raising future spending intentions in both Q4’23 and Q1’24. At time of writing, hyperscaler capex is expected to exceed $170bn in 2024, representing growth of 44% y/y. This is sharply higher than earlier expectations of +26% after Q4 results, and +18% at the beginning of the calendar year. According to Gartner, AI servers will account for nearly 60% of hyperscaler total server spending in 2024.

To date, the greatest beneficiary of AI infrastructure spending has been Nvidia as its GPU chips sit at the epicentre of the new AI architecture. In its most recent quarter, the company registered datacentre revenues of $18.4bn, a remarkable 409% y/y increase. Growth at this scale is extremely unusual in technology history, leading many to suggest that AI spending is a ‘bubble’. We strongly disagree and consider instead that we are early in the accelerated buildout of a general purpose technology.

Source: NewStreet Research - Company Report

Building the AI rails

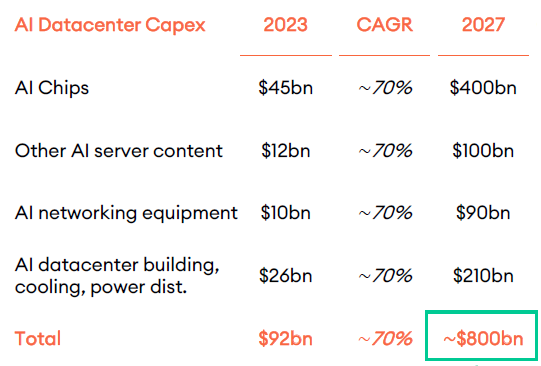

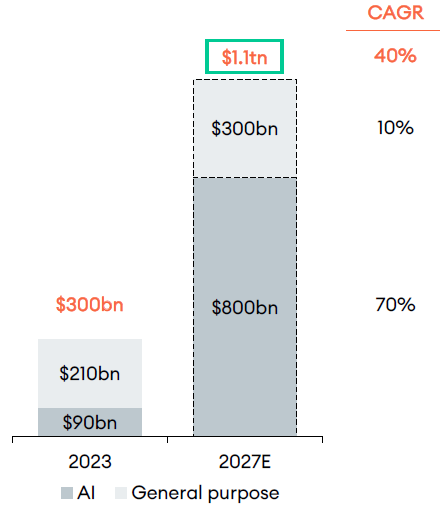

Sizing the AI infrastructure opportunity is difficult to say the least – in last year’s paper we had the temerity to suggest that AI capex “might exceed $100bn”. Since then, Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, has sized the AI market at $1Trn while Dr Lisa Su, CEO of rival AMD, has suggested the market for AI chips will reach $400bn by 2027, which including other component, system and networking costs implies an $800bn opportunity. At face value this suggests that AI spending could increase at a 70% CAGR through 2027 by which time it would reach c.0.8% of global GDP.

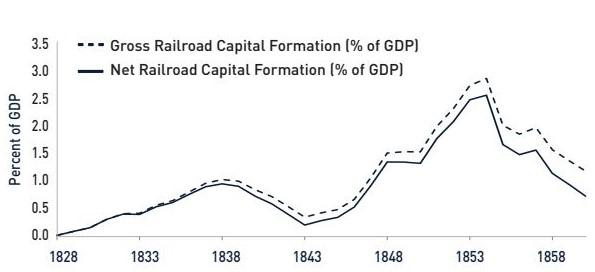

This would be extraordinary, but not unprecedented given that between 1830-1839, US railroad investment increased from 0.2% of GDP to just above 0.9% by 1839, corresponding to a 31% CAGR in nominal terms. After a digestion period, railroad investment reaccelerated, averaging 1.7% of GDP between 1850 and 1859. This astonishing period included a blow-off (bubble) phase after 1850, with investment peaking at 2.6% of GDP in 1854. At the height of the equivalent UK railroad boom, investment averaged 7% of GDP for three years. More recently, the dotcom period witnessed telecom companies spend $1trn (in today’s money) building out the Internet during the five years following the Telecommunications Act of 1996. While both historic parallels are useful reminders that infrastructure builds often end badly, current AI spending appears to us to be in its infancy.

The biggest opportunity.

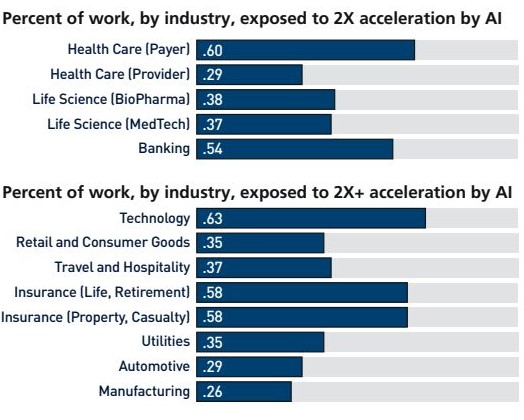

Underpinning AI spending is the scale of the AI opportunity, reflecting its would-be general purpose technology (GPT) status. Because it addresses knowledge work, economist Erik Brynjolfsson has described AI as “the ultimate GPT – the most general of GPTs”. Accenture estimates that as much as 40% of all working hours will be supported or augmented by language-based AI while McKinsey believe that generative AI could automate 30-50% of tasks in about 60% of occupations, adding the equivalent of between $2.6-4.4trn in economic output annually by 2030.

These longer-term opportunities are buttressed by early AI monetisation. Less than four years after launching a ‘capped profit’ arm in 2019, OpenAI is said to have reached a $2bn revenue run-rate with more than 92% of the Fortune 500 as customers. Meta has also demonstrated its ability to monetise GenAI by improving advertiser ROI and reducing the cost of customer acquisition. Enterprise adoption of copilots (AI-powered companion software) and premium AI-enabled products has also been encouraging. These tools enable knowledge workers to be more productive; Github Copilot (launched by Microsoft in collaboration with OpenAI in 2022) is helping software developers code up to 55% faster by writing 46% of the code. Lexis+ AI – a legal GenAI assistant from RELX – allows users to “draft clauses, legal documents.. and summarise case law.. (and) the reasoning behind the case”. Law enforcement technology provider Axon recently announced ‘Draft One’, AI-powered software capable of auto drafting police reports based on body-camera footage, saving officers an hour per day on paperwork; in Colorado, police experienced an 82% decline in time spent writing reports. Payment provider Klarna also announced it had replaced 700 full-time contact centre employees with AI agents saving the company $40m per annum. These are early glimpses into AI innovation and disruption, less than two years after the launch of ChatGPT.

Source: The College of William & Mary, December 2014

Source: The Generative AI Handbook

Happening now

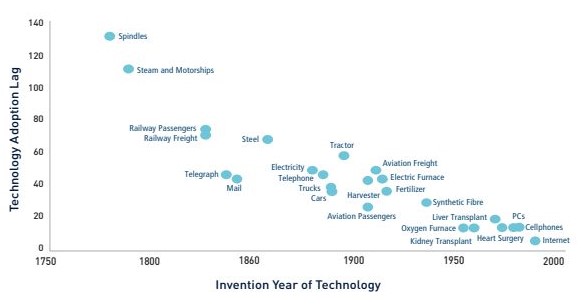

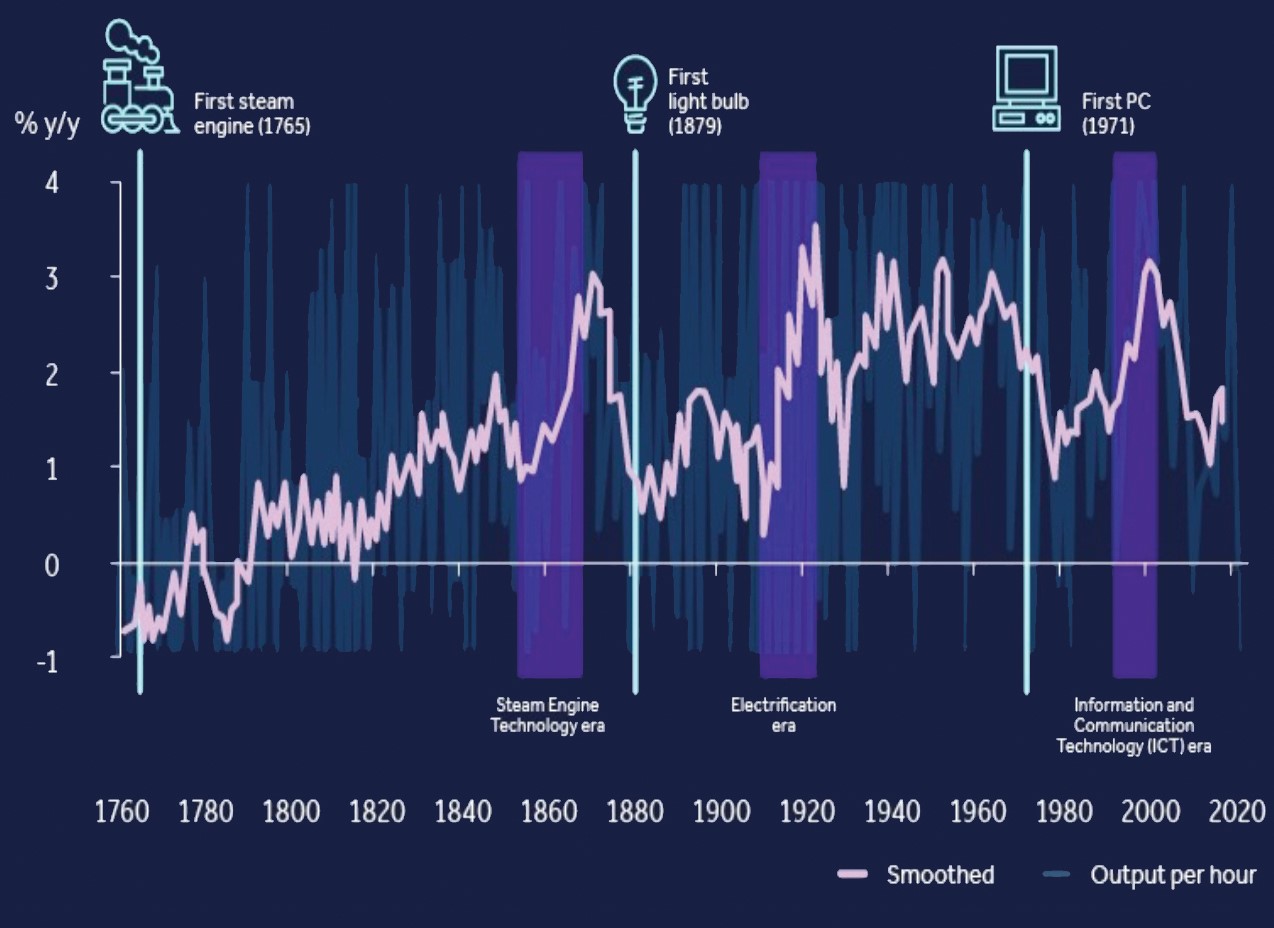

Rapid adoption and monetisation of nascent AI tools points to a faster than expected diffusion rate. History shows that the delay between invention and widespread use of new technologies has fallen significantly over time, while analysis of earlier GPTs by the Brookings Institute suggests that implementation lag halves with each successive GPT: 80 years for steam, 40 years for electricity, and 20 years for ICT. We expect AI to take less than 10 years to diffuse widely as it ‘stands on the shoulders of giants’ – technologies such as cloud, internet, leading edge semiconductors and billions of smartphones. Key AI breakthroughs did not happen overnight; the Cloud is nearly 20 years old. NVIDIA has been designing GPUs since 1999. Billions of smartphones and other connected devices have created vast datasets for training AI models and a near-ubiquitous channel for its distribution.

The idea of rapid AI diffusion is visible in real-world developments that include growing recognition among policymakers of the importance of AI and the need to address it through legislation with the number of AI-related bills passed into law increasing from just one in 2016 to 37 by 2022. The Hollywood writers’ strike in May 2023 was another notable development as 11,500 film and television writers began industrial action amid concerns around the AI’s role in scriptwriting, fearing that AI-generated scripts could undermine writers’ work and compensation. While some investors may be concerned about the risk of slower AI diffusion, the actions of those most exposed to the technology and legislators charged with controlling it suggest otherwise.

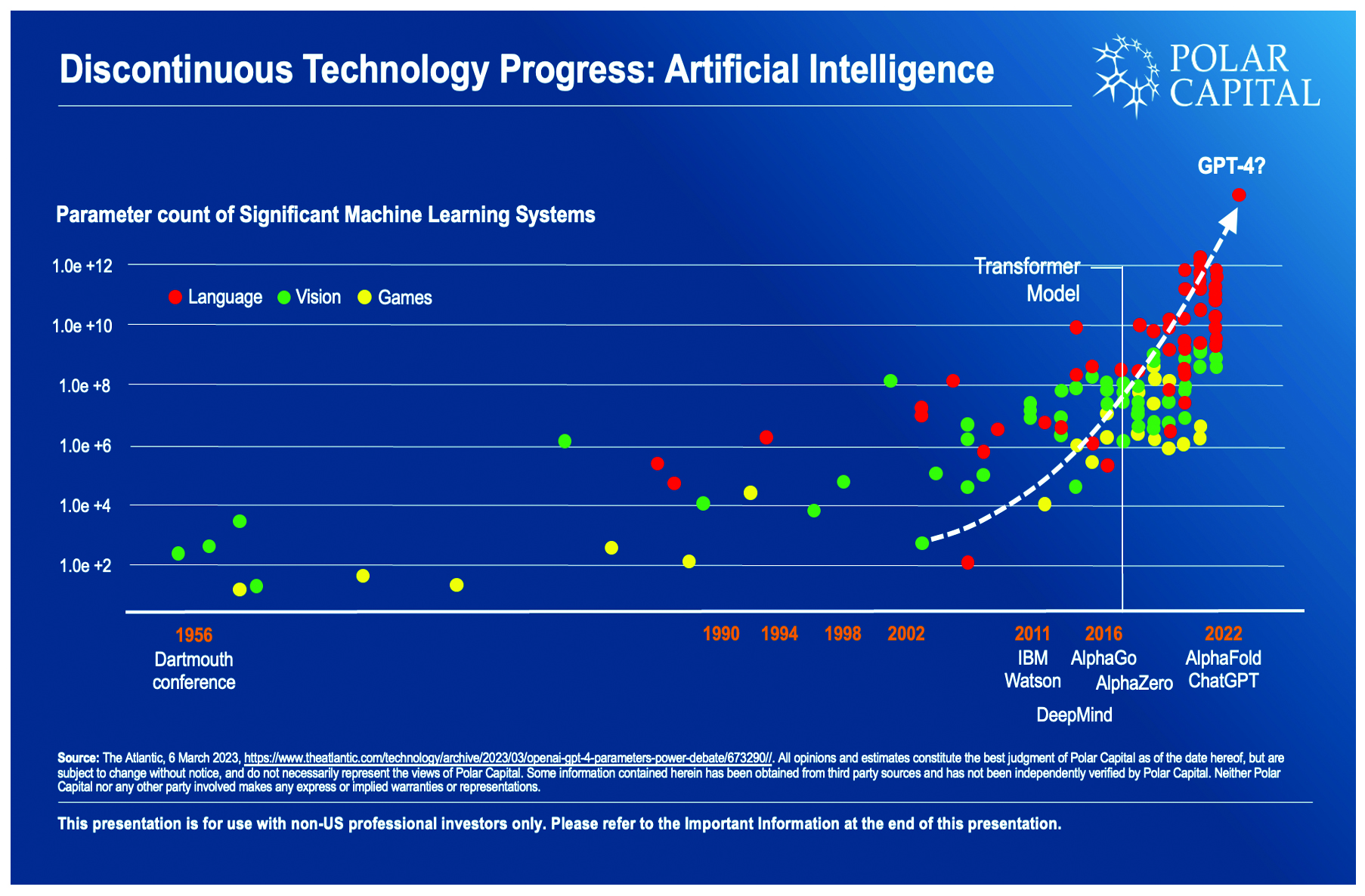

A model of improvement

Diffusion, monetisation, and corresponding capex are highly dependent on continued AI model progress. We believe the advent of the transformer model in 2017 represented a key breakthrough which is why we describe it as the ‘Bessemer moment for AI’. As with steel in 1856, this breakthrough has resulted in discontinuous technology progress; the parameter count of OpenAI’s GPT-4 (2023) is rumoured to be one million times larger than the DeepMind model that beat Lee Sedol at Go just seven years ago. Higher parameter counts have significantly increased the learning capacity of AI models, enabling them to handle a broader range of general-purpose tasks.

Recent model progress includes multimodality (able to analyse images and audio) and far larger token context windows (the amount of information that can be processed in any prompt). In February, OpenAI announced Sora, a remarkable AI ‘text-to-video model’ able to generate video based on descriptive prompts with “an emergent grasp of cinematic grammar”. The furious pace of model improvement recently saw Google’s Gemini Ultra become the first model to exceed the ‘human expert performance’ threshold on MMLU, an AI benchmark which measures knowledge across 57 subjects. Improved performance is also helping ameliorate earlier technology challenges with newer LLMs such as GPT-4 experiencing lower hallucination rates (incorrect model outputs). The expected launch of OpenAIs GPT-5 over the summer as well as the launch of Meta’s 425bn-parameter Llama 3 and Amazon’s 2trn parameter Olympus will serve as important waypoints to assess continued AI model progress.

Source: Comin and Mestieri, 2017

Source: The Atlantic, March 2023

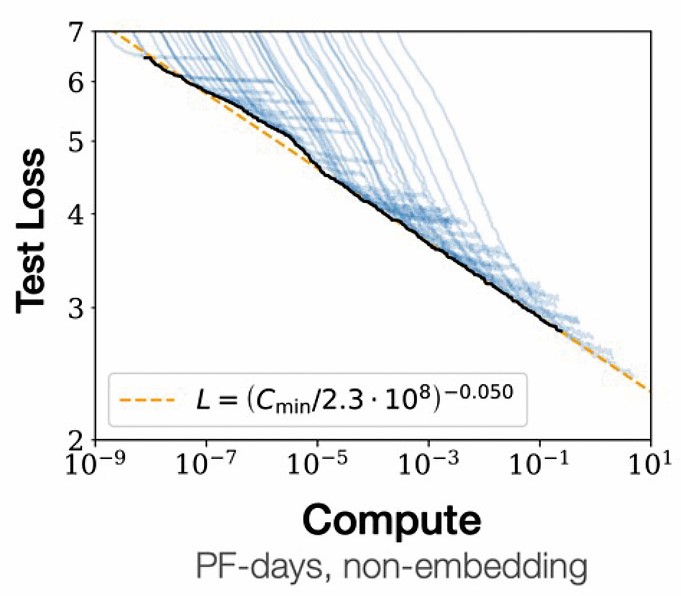

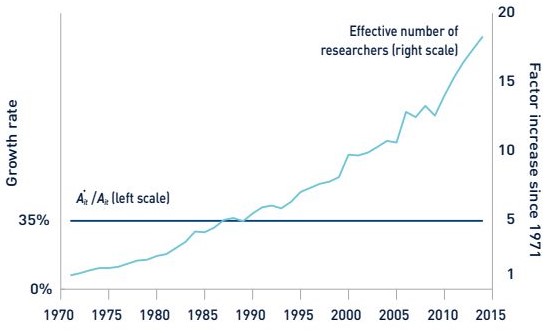

Our confidence in continued AI progress is underpinned by scaling laws which have so far predicted improvements in model performance based on increasing model size, the amount of training data and computing power applied. This is a complex topic to tackle here, but to us it is highly reminiscent of Moore’s Law, which famously stated that he number of transistors on a microchip would double approximately every two years. Humans struggle to model non-linear change, but Moore’s Law held true for many decades, predicting the exponential progress of semiconductors that followed. We believe that for as long as they hold, scaling laws predict a continued non-linear pace of AI model improvement and ever-greater investment required to stay on the curve. In a recent interview, Mark Zuckerberg defended Meta’s decision to significantly increase AI spending with reference to scaling laws:, “I think it’s likely enough that we’ll keep going. I think it’s worth investing the $10bns or $100bn+ in building the infrastructure.”

General intelligence

Zuckerberg’s excitement (and capex plans) reflects an apparently shortening timeline to artificial general intelligence (AGI), a point where AI might achieve the cognitive abilities of humans across a wide range of tasks. This would have seemed remarkable - crazy even – just a few years ago, but within the AI community, AGI is widely considered attainable in the near future. Founder of DeepMind Demis Hassabis has said AGI could be less than a decade away, while Shane Legg, Google’s chief AGI scientist, believes there is a 50% chance of general intelligence by 2028. Sam Altman also believes it could be reached within the next four or five years. A shortening timeline to AGI might make sense of a series of peculiar recent AI developments including the late 2023 debacle at OpenAI when Altman himself was fired and rehired in a matter of days, as well as decision by Geoffrey Hinton (‘The Godfather of AI’) to leave Google in May 2023 so he “could talk about the dangers of AI”. It might also explain why Altman has mooted the idea of raising $7trn – twice the size of UK GDP - to ‘reshape the semiconductor industry’. After all, if we are indeed close to achieving AGI, the world is going to need a lot of chips.

Welcome to the AI-era

We expect AI to profoundly change the world. At a prosaic level, AI should deliver a significant productivity boost, as was the case with prior GPTs. Current expectations for US productivity to average c.1.4% this decade look mismodelled; GS believe that AI could increase US productivity by 1.5% annually over the next decade, while Erik Brynjolfsson expects US productivity to average “at least 3%”.

Source: OpenAI, 2020

Source: Kendrick, 1961, Syverson, 2013

Risk to jobs

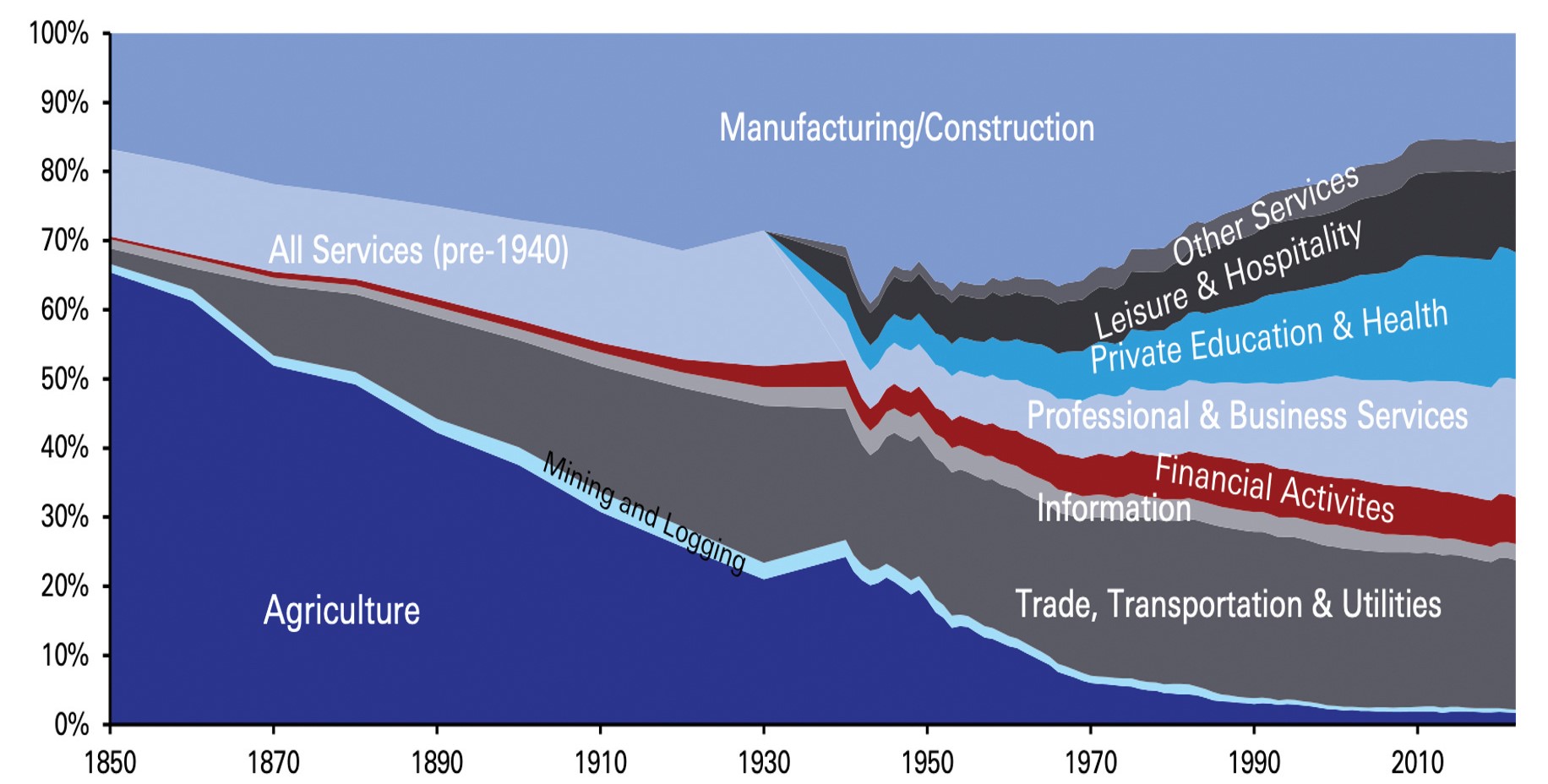

If so, the coming decade could be “the best ever” although we acknowledge that concerns about AI risk to jobs is understandable given its scope and pace of AI improvement. However, history demonstrates that humans have adapted well to prior technology disruption; in 1850, agriculture explained two-thirds of US jobs before mechanisation steadily reduced this to just 4% by 1970. Despite this, and subsequent technology innovations, median G7 unemployment has “oscillated based on economic cycles, rather than any technological waves” since 1750.

While knowledge work is in the crosshairs of this new GPT, we expect the first wave of AI to complement rather than substitute human work, as is the usual pattern of technology change. Even when AI adoption becomes more disruptive all is far from lost, as the agricultural experience demonstrates. While focus will inevitably fall on jobs ‘lost to AI’ there should be many more made possible by the union of human + machine.

Unfortunately, we cannot know what new opportunities will be made possible by AI. However, we do know that earlier tools and GPTs created opportunities that were previously unthinkable. For instance, the sewing machine changed the relationship between humans and clothing. Previously, clothes were prohibitively expensive; Singer’s sewing machine (1855) transformed this by increasing stitches per minute 22-fold, reducing the time it took to produce a shirt from 14 ½ hours to c.1 Today, apparel is a $2trn industry.

Likewise, the telegraph – the precursor of all modern communication systems – “freed communication from transportation”. By changing the relationship between information and distance, the telegraph (1837) challenged price arbitrage, changed the way wars were waged, created the ‘information industry’ (news agencies such as Reuters and AP) and gave life to the first ‘fintech’ application – wire transfer – introduced by Western Union in 1871.

Hopefully these two lesser known case studies help explain why we know AI will create massive new markets, and challenge existing relationship that exist today. However, we cannot yet know what form these will take, just as Morse – who tried to sell his telegraph system to the US government for $100,000 - did not fully understand its commercial potential.

Idea Generation

We know that earlier technology tools and GPTs have changed relationships. Our early bet is that AI changes the relationship between people and ideas. Transportation technologies (horse, canals, railroads, containers, aviation etc) tamed distance by transforming the movement of physical goods (freight, people). Communication technologies (telegraph, telephone, internet etc) tamed distance by changing the velocity of information. We suspect AI will transform the speed of knowledge creation after years of declining research productivity. The ability to inject limitless AI into research should meaningfully accelerate scientific progress, and unlock new ideas, just as the telegraph acted as “an agency for the alteration of ideas”.

16 July 2024*

*Data and statistics referenced within the Investment Manager’s report may have changed between the financial year end and the date of publication.

Source: Haver Analytics, US Census, Deutsche

Source: Bloom et al, 2020